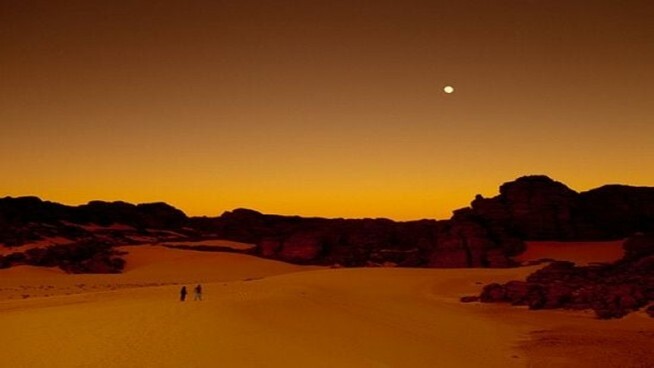

Large reservoir of water discovered beneath the Sahara

-

A geological map drawn up by British scientists shows that Africa rests on a vast reservoir of groundwater, with the largest aquifers located in the north, Alan MacDonald, the geologist who led the research, recently explained

A geological map developed by British scientists shows that Africa rests on immense groundwater reserves, with the largest aquifers located in the north, Alan MacDonald, the geologist who led the research, recently explained.

The total volume of groundwater amounts to half a million cubic kilometers, an amount equivalent to twenty times the annual rainfall across Africa. About half of these reserves—dating back some 5,000 years—are found in Libya, Algeria, and Chad, coinciding with part of the Sahara Desert, MacDonald explained.

“These large water reservoirs could alleviate the situation of more than 300 million Africans who lack access to drinking water, as well as improve crop productivity,” said this expert from the British Geological Survey.

The study, which also includes experts from University College London, indicates that the volume of water in the aquifers is 100 times greater than the amount found on the surface. This is the first study to cover all of Africa’s groundwater reserves and includes a series of maps published in the scientific journal “Environmental Research Letters”. For its preparation, the experts compiled hydrological maps prepared by different African countries as well as the results of 283 previous regional studies.

In North Africa, the pockets of stored water are 75 meters thick and protected by extremely hard rocks like granite, which has come as a surprise to researchers. However, these aquifers are not refilled by water from recent rainfall filtered through the earth; their reserves date back approximately 5,000 years. At that time, the Sahara was a verdant landscape, with numerous lakes and savannah vegetation, but it became the largest hot desert on the planet 2,700 years ago after a slow process of desertification.

Furthermore, geologists have discovered large reserves on the coast of Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, and parts of Guinea-Bissau, as well as in the Congo and the border region between Zambia, Angola, Namibia, and Botswana. In many arid and semi-arid areas of the continent, it would be possible to extract water to supply the population—although not for intensive farming—using hand-held wells, given that the reserves are found at depths of less than 25 meters.

The exception is some northern countries like Libya, where aquifers lie at depths of 250 meters or more, requiring more expensive and complex infrastructure. “The Horn of Africa has the smallest aquifers, but there would still be enough water for human consumption, and it wouldn’t be expensive to extract it through wells. Furthermore, there wouldn’t be a need to invest in water treatment, because the quality is so good,” MacDonald added.

Only 5% of Africa’s fertile land is irrigated, and demographic projections for the coming decades indicate that population growth will increase the demand for water for consumption and crop irrigation.

MacDonald cautioned, however, that tapping these large pockets of water through large boreholes may not be the best strategy for increasing supply and expressed concern that low rainfall could reduce aquifer levels.

“In most of Africa, rainfall is not sufficient to replenish aquifers, so I would recommend not extracting more water than is replenished each year by rainfall,” the geologist advised.

“An aquatic treasure in the middle of the desert”

The discovery was made possible through a combination of seismic analysis and deep drilling, which confirmed the presence of a freshwater reserve in the heart of the desert.

For Dr. Amina Zohar, leader of the research team, this discovery opens up an unsuspected horizon: “It’s an aquatic treasure in the middle of the desert, a resource that could transform lives and ecosystems.”

Beyond its scientific value, the human impact is evident. Mohamed Saleh, a local farmer, sums up the hope it inspires: “We struggle every season to find enough water for our crops. The idea that a vast reserve exists right beneath our feet is almost unreal.”

Water for drinking, planting, and climate resilience

Access to this enormous reserve could improve the supply of drinking water in the Sahel countries, where rainfall is increasingly unpredictable. It would also pave the way for new agricultural practices that would reduce dependence on rainfall and strengthen food security.

Researchers emphasize that the use of noninvasive remote sensing and geophysical technologies has made it possible to map the lake without disturbing the fragile Saharan ecosystem.

A historic opportunity for the region

If managed sustainably, this underground reserve could become an ecological and economic engine for millions of people:

- Boosting agriculture and industry in arid areas.

- Strengthening resilience to climate change.

- Serving as a model for other projects in the world’s deserts.

“This discovery is not just about water,” the experts explain, “but about the real possibility of transforming the Sahara into a land of opportunity.”